Stories

Childish

In this extract, Robert Macfarlane considers how children experience wild spaces

"Children have many more perceptions than they have terms to translate them,"wrote Henry James, memorably, in his Preface to What Maisie Know (1897). But it might be truer to say that 'Children have many more terms than we have perceptions to translate them.' For the speech of young children is subtle in its intricacies and rich in its metaphors. It is not an impoverished dialect of adult speech. Rather, it is another language altogether; impossible for adults to speak and arduous for us to understand. We might call that language 'Childish': we have all been fluent in Childish once, and it is a language with a billion or more native speakers today — though all of those speakers will in time forget they ever knew it.

Five or six years ago I met a remarkable person called Deb Wilenski. Deb understands Childish better than any other adult I have met. In her thirties she was a researcher specializing in primate behaviour and psychology. She undertook fieldwork with rhesus macaques in Cayo Santiago, and with baboons in Namibia, following a pack in the high orange hills of the country's south-west. She was studying how the baboons oriented and navigated themselves, and how intent and knowledge were communicated between members of the troop. "The baboons would meet and mingle in the mornings,"she told me, "flow their many different ways down into the valleys, and then miraculously coincide, miles away, hours later, as if each knew where the invisible rest of the group was heading."Up in the Namibian hills, looking out over the landscape, with seventy-four pairs of baboon eyes also looking out over the same relatively simple terrain (slopes, gravel plains, dry riverbeds), she began to realise how she and the baboons were "seeing different things: the routes and resources, the ways through the land, the landmarks, were all multiple".

From baboons, Deb turned to young children, but continued her interest in 'multiple' landscapes. She left anthropology and academia behind, and became involved in outdoor pre-school education, inspired in the first instance by the forest kindergartens of Scandinavia and by Loris Malaguzzi, the founder of the Reggio Emilia approach, who emphasized the need to listen to children rather than to instruct them. Deb wanted to let children lead her into landscapes, rather than the reverse — and to explore their imaginations as they explored places. She began working with groups of children over several months, taking them often to the same areas of forest or wild ground and then letting them find their own ways into the woods. As they discussed their findings with one another, Deb listened — and this was how she began to comprehend at least some of what Malaguzzi once called 'the hundred languages of children'.

One of the first places Deb went was Wandlebury, the area of mixed beech woods and grassland that lies on the chalk uplands south of Cambridge, near to my home. Wandlebury is a child's delight: there is an Iron Age ring-fort with a deep outer ditch, twelve feet deep in places, around which you can run in an endless circle. Beyond it, among the trees, is a network of forking and interlacing paths so complex that it seems impossible to trace the same route twice. At Wandlebury the children led and Deb followed. She was careful not to intervene in their plots and plans, except when safety required it. Slowly, she began to make records of the children's conversations as they explored the area. She mapped the routes they followed, the dens they built out of dead wood and fallen branches, the places of rest and shelter they settled upon and the doorways they found, and the language they used to describe what they discovered each day.

In the winter of 2012, together with an artist called Caroline Wendling, and encouraged by an organization called Cambridge Curiosity and Imagination, Deb began work with a reception class from a primary school in Hinchingbrooke, north Cambridgeshire. For three months, each Monday morning she and Caroline went with around thirty four- and five-year-old children into the country park that bordered the school's grounds. The eve of that first Monday was — echoes of The Dark Is Rising - a night of blizzards. Heavy snow lay on the land the next morning, and there ensued one of the harshest winter-springs of recent years in the south of England. "It was cold when we began in January,"remembered Deb later, "and it was still cold when we ended in April. What was amazing was that nobody seemed to mind."

Hinchingbrooke Country Park consists of 170 acres of meadow, lake, wood and marsh, lying a mile or so west of Huntingdown, and bounded on one side by a dual carriageway and on another by a hospital car park. It is a landscape of contrasts: tall old pines with dark short sightlines give way to meadows that lead down to the edge of water. The children were free to explore within the park, and the hours they spent there were unstructured by commitment. Each Monday morning was spent in the landscape, each afternoon back in the school further investigating "the real and fantastical place that the park was becoming".

Deb watched and listened over the months, and tried to record without distortion how the children 'met' the landscape and how they used their bodies, sense and voices to explore it "with imagination and with daring". She sought to follow how the children navigated and oriented themselves: the "visible and invisible traces through the forest"that they left, the "lines drawn on paper"and "words [and stories] that connect one place to another".

It was clear that the children perceived a drastically different landscape from Deb and Caroline. They travelled simultaneously in physical, imagined and wholly speculative worlds. With the children as her guides, Deb began to see the park as 'a place of possibility' in which the 'ordinary and the fantastic' - immiscible to adult eyes — melded into a single allow. No longer constituted by municipal zonings and boundaries, it was instead a limitless universe, wormholed and Möbian, constantly replenished in its novelty. No map of it could ever be complete, for new stories seethed up from its soil, and its surfaces could give way at any moment. The hollows of its trees were routes to other planets, its subterrane flowed with streams of silver and its woods were threaded through with filaments of magical force. Within it the children could shape-shift into bird, leaf, fish or water.

Each day brought different weather, and each weather different worlds. The snow of the first week was white to Deb's and Caroline's eyes, but to the children it was technicoloured: 'yellow at the edges' and 'green at the top of the trees' to a boy called Filip; a 'pink forest' to Thomas. When the thaw eventually came, it left a world 'of newly made mud', The smooth snow-sward gave way to new textures and dimensions: slipperiness, sinkholes, ruts and rivulets. The wood became suddenly deep to the children, as the mud sucked and clutched at them. When rain came, the children were drawn to water and waterways. One of the children, Cody, became fascinated by the disappearance and reappearance of running water within the park: how pond connected to lake, stream to puddle. In ways that were in contradiction of gravity, but consistent with the physics of his own imagination, Cody started to account for the existence of visible water by means of an unseen network of what he called "secret water"that ran unprovably beneath the ground. He took to a kind of dowsing, pacing out on the surface the flow-lines of this secret water and — as Deb put it — helping her "realize that the land we are exploring sits on top of a whole other land, subterranean, that shares with ours a single, continuous, touchable surface"

Cody found entrances to this underworld by reeds and tree roots — as every child found doorways to the realms they named into being. These doors led to dangerous places a well as 'good spots', and the landscape was soon crowded with them, like the beehive cells of the Skelligs. The drawings the children made in the afternoons were also densely doorwayed: mouse holes, tunnel mouths, portals. None of the doors the children drew, Deb noticed, had locks. The doors appeared and disappeared, but always opened both ways.

As well as opening doors, the children made dens: the doors allowing access and adventure, the dens permitting retreat and shelter. Young children are, as all parents know, natural den-makers. Indoors, they curl up in bedclothes, they string sheets between chairs, they prop cushions in corners, they crawl under tables, they shut themselves into carboard boxes — fashioning nests, bolt-holes, setts and holts. Outside they steal into the hearts of hedges, improvise shelters from packing cases and plastic bags, or make rickety wigwams and lean-tos out of branches. Children's literature is dense with dens: the hollow-tree hideout that because the redoubt of the feral siblings in BB's Brendon Chase (1944), the scavenged shanty-den of Stig of the Dump down at the bottom of the chalk pit or the piratical stockades founded by Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn.

In the architecture of dens, function is subservient to form: it doesn't matter that a den's loose-ribbed walls would keep out no wind, or that its entrance can be entered only at a crawl. A fallen trunk will serve as a roof ridge, against which sticks and branches can be leaned. Yellowing leaves are gathered and piled to make a heatless fire, around which the children can sit, warming their hands in its light. Old dens are cannibalized to make new dens, and no one structure seems to last more than a season. The woods at Wandlebury hold dozens of dens at any one time, and when I see them there together and in such number, seen between the beeches, there is a curiously ethnographic feel to the encounter: as if the dens are the evidence of a lost tribe, discovered in a region that is barely reachable or known.

Which, of course, is what they are: the tribe being children, the region being childhood, and the ethnographers being adults. Not that we wholly lose our fascination with dens as we age. "After one of his shipwreckings in the Odyssey,"notes Tim Dee:

Odysseus clambers up a hill from a beach and crawls beneath two olive trees, one wild and one domesticated, and makes a nest there from the dropped leaves of both. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, walking in the Lake District in June 1801, found "a Hollow place in Rock like a Coffin — exactly my own Length — there I lay and slept. It was quite soft."

In his classic study of intimate places, The Poetics of Space (1958), the French phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard writes at length about our lifelong dream-need for hollows and huts. Traversing ornithology, psychology, architecture and literature, Bachelard discovers a family of den-like recessed spaces — corners, birds' nests, cellars, attics, chests, caverns, walled gardens (the hortus conclusus) - that continue to exert a fascination upon the mind even as it ages, because they "shelter day-dreaming". He calls the readiness to be astonished by such spaces 'topophilia' (place-love), but I think we might also name it 'wonder', 'innocence' or even just 'happiness'.

Macfarlane, R. (2015) Landmarks London: Hamish Hamilton. (Loc 4753 — 4833)

Badger or Bulbasaur? Have children lost touch with nature? suggests that children have an affinity for creatures, but that they are more likely to know about synthetic creatures such as Pokémon rather than wild animals. It suggests that knowing the names of wild creatures strengthens our creativity and engagement with the natural world.

In contrast, Pokémon — from bugs to blockbuster describes how Pokémon arose from its creators love of insect life, and a desire to share the pleasures of entomology with city children "the joy of discovery, of offering children, many of whom were born into urban environments, the opportunity to experience the thrill of finding and cataloguing creatures and sharing their experiences with their peers"

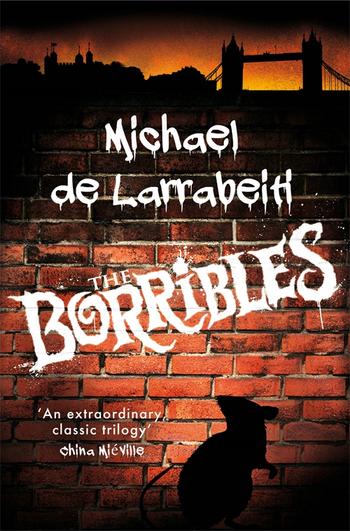

The Borribles

Not everyone experiences the natural world as a place of wonders. For the Borribles, the urban environment is the safe and familiar one, and the emptiness of Rumbledom Common is a chilling wilderness

Sam took them through many deserted roads and gardens and strange silent streets, hauling the old cart across the steep hills which guarded the borders of Rumbledom. The horse strode out purposefully, head high and legs thrusting hard, the colour of his coat alternating between deep purple and gold as he entered and left the quiet pools of light which fell gracefully from the tall white swan-necks of the concrete street lamps.

Sam trudged on, from Brookwood Road to Elsenham Street, and into Augustus where the slope began in earnest. Up Albert Drive and Albyn Road, through Thursley Gardens and along Seymour Road and Bathgate Road, up Somerset Road at last and the slope flattened and the sky lightened and turned blotchy, like yesterday's porridge. And a cold dark wind came across a boundless space and numbed the intent of the Adventurers as they peered from beneath the warm canvas. The crisp air lined their lungs with ice, chilling their blood at the heart. Sam hesitated. One last road to cross - Parkside. He shook his head and neighed valiantly, and went out into the green and black stillness that was Rumbledom.

Bingo guided the horse and cart to a large clump of trees not far into the wilderness. The wintry light of morning glinted without friendliness on a sheet of water nearby. 'Bluegate Gravel Pit, Disused', said the map.

Faces

Amongst many resources available through the National Library of Scotland you will find Faces a story about a Kelvingrove park keeper, the park visitors and the personas we adopt. This film makes me want to make masks outdoors with my class, and talk about the differences between the selves we show and the feelings we keep inside.

You can find tips on papier mache mask making, with and without ballons, on Youtube. Here's just one example.

Wisdom Sits In Places

Many of these places are also encountered in the country of the present as material objects and areas, naturally formed or built, whose myriad local arrangements make up the landscapes of everyday life. But here, now, in the ongoing world of current concerns and projects, they are not apprehended as reminders of the past. Instead, when accorded attention at all, places are perceived in terms of their outward aspects – as being, on their manifest surfaces, the familiar places they are – and unless something happens to dislodge these perceptions they are left, as it were, to their own enduring devices. But them something does happen. Perhaps one spots a freshly fallen tree, or a bit of flaking paint, or a house where none has stood before – any disturbance, large or small, that inscribes the passage of time – and a place presents itself as bearing on prior events. And at that precise moment, when ordinary perceptions begin to loosen their hold, a border has been crossed and the country starts to change. Awareness has shifted its footing, and the character of the place, now transfigured by thoughts of an earlier day, swiftly takes on a new and foreign look.

Consider in this regard the remarks of Niels Bohr, the great theoretical physicist, while speaking in June of 1924 with Werner Heisenberg at Kronberg Castle in Denmark, Bohr's beloved homeland.

Isn't it strange how this castle changes as soon as one imagines that Hamlet lived here? As scientists we believe that a castle consists only of stones, and admire the way the architect put them together. The stone, the green roof with its patina, the wood carvings in the church, constitute the whole castle. None of this should be changed by the fact that Hamlet lived here, and yet it is changed completely. Suddenly the walls and ramparts speak a different language. The courtyard becomes an entire world, a dark corner reminds us of the darkness of the human soul, we hear Hamlet's "To be or not to be." Yet all we really know is that his name appears in a thirteenth-century chronicle. No one can prove he really lived here. But everyone knows the questions Shakespeare had him ask, the human depths he was made to reveal, and so he too had to be found a place on earth, here in Kronberg. And once we know that, Kornberg becomes quite a different castle for us. (quoted in Bruner 1986:45)

Thus, by one insightful account, does the country of the past transform and supplant the country of the present. That certain localities prompt such transformations, evoking as they do entire worlds of meaning, is not, as Niels Bohr recognised, a small or uninteresting truth. Neither is the fact, which he also appreciated, that this type of retrospective world-building – let us call it place-making- does not require special sensibilities or cultivated skills. It is a common response to common curiosities – what happened here? who was involved? What was it like? Why should it matter? – and anyone can be a place-maker who has the inclination. And every so often, more or les spontaneously, alone or with others, with varying degrees of interest and enthusiasm, almost everyone does make places. As roundly ubiquitous as it is seemingly unremarkable, place-making is a universal tool of the historical imagination. And in some societies at least, if not in the great majority, it is surely among the most basic tools of all.

Prevalent though it is, this type of world-building is never entirely simple. On the contrary, a modest body of evidence suggest that place making involves multiple acts of remembering and imagining which inform each other in complex ways (Casey 1976, 1987). It is clear, however, that remembering often provides a basis for imaging. What is remembered about a particular place – including, prominently, verbal and visual accounts of what has transpired there – guides and constrains how it will be imagined by delimiting a field of workable possibilities. These possibilities are then exploited by acts of conjecture and speculation which build upon them and go beyond them to create possibilities of a new and original sort, thus producing as fresh and expanded picture of how things might have been. Essentially, then, instances of place-making consist in an adventitious fleshing out of historical material that culminates in a posited state of affairs, a particular universe of objects and events – in short, a place-world – wherein portions of the past are brought into being.

*

Landscapes are always available to their seasoned inhabitants in more than material terms. Landscapes are available in symbolic terms as well, and so, chiefly through the manifold agencies of speech, they can be "detached" from their fixed spatial moorings and transformed into instruments of thought and vehicles of purposive behaviour. Thus transformed, landscapes and the places that fill them become tools for the imagination, expressive means for accomplishing verbal deeds, and also, of course, eminently portable possessions to which individuals can maintain deep and abiding attachments, regardless of where they travel. In these ways, as N. Scott Momaday (1974) has observed, men and women learn to appropriate their landscapes, to think and act "with" them and as well as about and upon them, and to weave them with spoken words into the very foundations of social life. And in these ways, too, as every ethnographer eventually comes to appreciate, geographical landscapes are never culturally vacant. The ethnographic challenge is to fathom what it is that a particular landscape, filled to brimming with past and present significance, can be called upon to "say," and what, through the saying, it can be called upon to "do."

Basso, K. H. (1996). Wisdom sits in places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ( Loc 203 – 233, 1391-1394)